The increasing emphasis on performance criteria as the measure of design value stunts architecture in many ways. One of the more insidious is the reification of current conditions of building production, that is assuming that

- current economic and political constraints on the construction, financing, use and planning of the built environment will always prevail; and

- architecture must be “realistic,” meaning that it must operate within them.

Put another way, architecture’s job is to figure out how to contort (I would not say “meet”) the needs of society so as to be amenable to these reified constraints.

Yes, people’s need for buildings is immediate and pressing and cannot wait for a possible future in which the conditions of building construction may be different. Further, it is possible to create buildings under current conditions with more or less concern for ordinary people, more or less imagination, more or less awareness of the many scales and modes by which buildings shape our environment. That is to say, it is possible to design well or badly, to do it out of concern for people’s well-being or for personal gain.

Many architects amplify the prevailing market into a rationale for following the path of least resistance in their practices. If I had a nickel for every time someone has “reminded” me that architects need to make a living- well,I’d have a lot of nickels. I will stipulate that architects need to make a living. But this does not justify adopting the market as rationale for ceasing to think about how we live in larger terms. Our true purpose is to engage in this kind of questioning. We often underestimate the scope our projects offer for doing this.

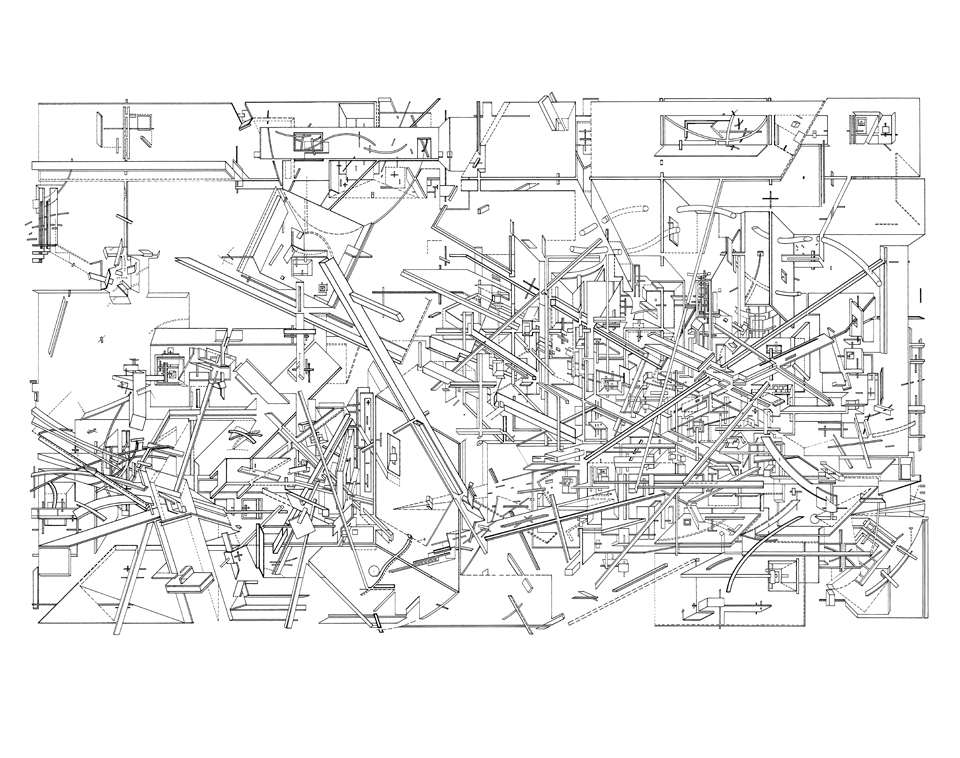

(An aside- our collective preoccupation with buildings as formal objects, often justified as “exploring new possibilities of inhabitable space,” is not the kind of questioning I’m talking about. Being honest with ourselves, we should recognize that much of the work done under this guise is at best equating architecture with sculpture. At worst, it is mindless idolatry of newness for its own sake.)

Winy Maas of MVRDV has posted a video of a presentation he made to urban planners in Glasgow that is inspiring in this regard. You could call it “the architecture of the impossible”. The issues his ideas address are very real: global warming, with its consequences for energy and water consumption, urbanization and population growth, mass population migrations, and the cost of infrastructure among others. What is remarkable is not only the imagination of his solutions, but the fact that, under present conditions, they are impossible. Not physically impossible, but politically impossible. In many cases this is because the level of political organization needed to carry out a project does not exist (yet). It makes sense for water-rich Sw itzerland to build a network of reservoirs to supply water to drier parts of Europe (see left), if only the political infrastructure existed to plan and build the accompanying distribution system. Why not cover south-facing mountainsides with photovoltaic panels? Well, again you would need a continent-wide distribution network to make the project economically feasible, not to mention a financial structure to pay for the project. Maas’s projects are impossible, but they argue for themselves as solutions to real problems and force us to ask, “Why are these things impossible? What is holding society back from realizing them?” Once there, the projects become arguments for changing the political and economic structures that make them impossible so that they become possible. In other words, the projects themselves become forces for change.

itzerland to build a network of reservoirs to supply water to drier parts of Europe (see left), if only the political infrastructure existed to plan and build the accompanying distribution system. Why not cover south-facing mountainsides with photovoltaic panels? Well, again you would need a continent-wide distribution network to make the project economically feasible, not to mention a financial structure to pay for the project. Maas’s projects are impossible, but they argue for themselves as solutions to real problems and force us to ask, “Why are these things impossible? What is holding society back from realizing them?” Once there, the projects become arguments for changing the political and economic structures that make them impossible so that they become possible. In other words, the projects themselves become forces for change.

This model for making architecture a force for social change involves two steps. First, architects must address problems that affect people’s lives (and no, “new possibilities of inhabitable space” is not such a problem). These problems must be sufficiently pressing to get people to think seriously about solutions they have never considered before, that may at first seem outlandish. Second, architects have to decide which of the conditions that circumscribe their work are actually not carved in stone, but could be changed if the necessary political will existed. Architecture thus works towards social change by demonstrating its benefits.

The scale of Maas’s projects in the video are vast- far beyond the scope of most architects’ practices (imagine having Switzerland as a commission!). But the model still works. On every project, we need to ask ourselves if we have accepted some constraint as immutable, when in fact it could be eased or removed by altering some human institution. This may not be possible immediately, but once we have demonstrated with a project that making such a change would be beneficial, we can begin to persuade people to make the change.

What we are talking about here is challenging current performance criteria. The all-too-common mindset, abetted by BIM and related developments, is to accept and quantify performance criteria as given, and to maximize a design with respect to those criteria. As I have argued in The Death of Drawing and on this blog, this mindset is fatal to architecture as a cultural and social force. Architects must challenge performativity in any way they can. One way to do this, suggested by Maas’s projects, is to turn performativity against itself by asking whether better answers can be found by suspending accepted performance standards.

The notion of “data-driven” design gets a lot of press these days, as if what contemporary architects need is more quantitative knowledge about how people use buildings and spaces. This idea rests on misunderstandings of architecture so profound as to beggar belief. But since the idea is so common these days, it appears worthwhile to spell out exactly why it is not only wrong but harmful.

The notion of “data-driven” design gets a lot of press these days, as if what contemporary architects need is more quantitative knowledge about how people use buildings and spaces. This idea rests on misunderstandings of architecture so profound as to beggar belief. But since the idea is so common these days, it appears worthwhile to spell out exactly why it is not only wrong but harmful.

The article in today’s

The article in today’s  Modern Movement, carried to an extreme. And there were two of them, doubling down on the claim of universality. No trylon-and-perisphere dialectic here: there was only one idea to represent.

Modern Movement, carried to an extreme. And there were two of them, doubling down on the claim of universality. No trylon-and-perisphere dialectic here: there was only one idea to represent.

The article by Michael Graves that appeared in the New York Times on September 1, 2012 created quite a furor, demonstrating how important this issue is in the minds of architects. The discussion in the architecture press subsided far too quickly. The role of drawing in architecture that he articulates and the consequences of its fading from practice should be a constant topic of conversation among architects. Take the time to read (or re-read)

The article by Michael Graves that appeared in the New York Times on September 1, 2012 created quite a furor, demonstrating how important this issue is in the minds of architects. The discussion in the architecture press subsided far too quickly. The role of drawing in architecture that he articulates and the consequences of its fading from practice should be a constant topic of conversation among architects. Take the time to read (or re-read)